Species Spotlight: Andrena, the Mining Bees

This guest blog is part of a series of articles written by Mount Allison students, as part of a partnership between Nature NB and the Applied Native Plants and Pollinator Conservation course. Thanks to Dr. Emily Austen and the students for this ongoing collaboration!

By Jada Ripley (jaripley@mta.ca), Student at Mount Allison University

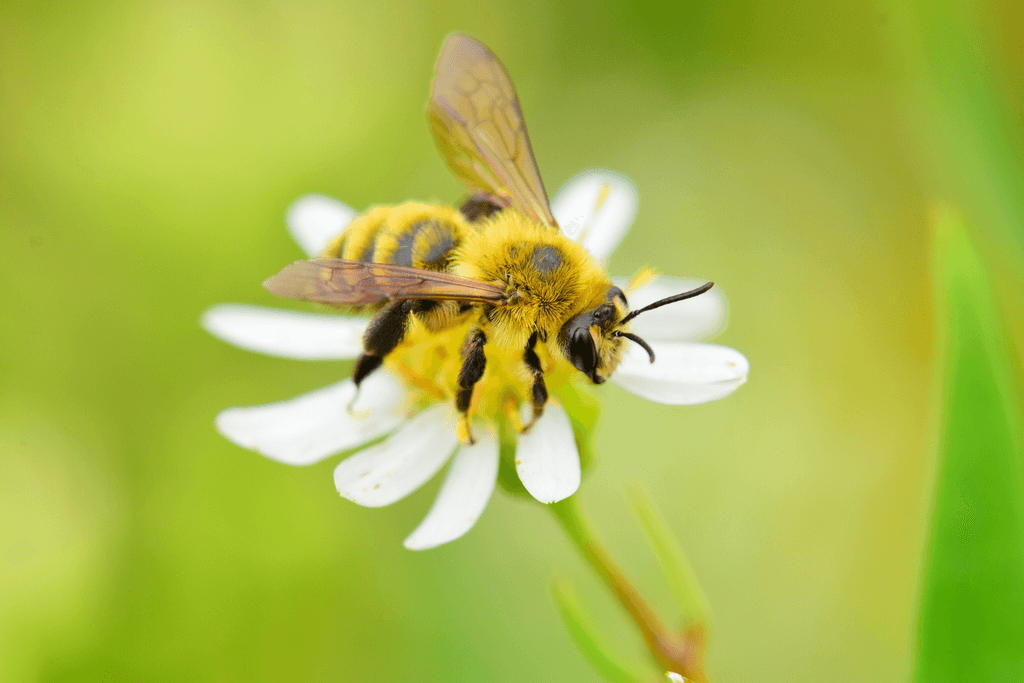

If you’ve ever spent time exploring the first wildflowers to bloom around your home in the early-Spring, you’ve probably seen some wild bees that look similar to bumblebees. But, these bees are much too slender, and typically much too small to be bumblebees. These bees were likely mining bees.

In New Brunswick, there are around 51 species of mining bees1. Some of these species are indistinguishable by the eye, and some are very unique2. Mining bees are smaller than honeybees, ranging from under a centimetre to a centimetre and a half1,2. They carry pollen loosely in the hairs on their hind legs— their scopae— which may be coloured tan, red-orange, or black like the hairs on the rest of their body1,3.

Mining bees are solitary4. So, unlike honeybees, these bees create their own nests where they live and support their young alone. These nests are built in the ground, which is why these bees are named “mining bees”. Nests are typically on flat ground with vegetative cover like trees, grass, and hedges4,5. But, many mining bees also build their nests on bare ground4,5.

Lydia Fravel, 2022. CC-BY 2.0

Mining bees can be observed throughout the warm seasons, but most mining bees will be seen in the early-spring or in the late-summer2,6,7. This is partially because many mining bees are specialists, so they only visit one type of flower to collect their pollen7. Specialist mining bees may visit early-spring flowers like willows and blueberries, or visit late-summer flowers like goldenrod and asters7,8. Other mining bees are generalists, so they visit a wide variety of flowers8. Because there is such a high abundance of mining bees with different floral specialties2, they are essential pollinators in New Brunswick. Mining bees also offer pollination services to a wide array of commercial crops including cranberries, lowbush blueberries, and apples7,8,9.

Mining bees face similar threats to all other groups of wild bees9,10,11. Mining bees are at-risk of pesticides, habitat loss, competition with non-native bees, and loss of floral resources for feeding9,10. Since pesticides are often sprayed in the early-spring when many mining bees emerge, they may be at higher risk of pesticide exposure than other late-emerging wild bees9. They may also be exposed to pesticide residue on flowers where they forage, or in the soil where they build their nests10.

Some mining bees experience more threats than others11. Specialist mining bees face greater threats than generalist mining bees11. Since specialists are dependent on a certain plant, if it disappears in an area, then they will be lost as well11. Even when specialists are dependent on a common plant, they can still be at greater risk because they often require specific at-risk environments, like wetlands11.

Bernie Paquette, 2022. CC-BY 4.0

If you’d like to help mining bees in your community and around your home, here are some actions you can take. Plant native flowers like goldenrod in your garden, or leave an un-weeded patch of your garden to grow naturally10. Consider planting a tree or shrub that attracts mining bees like a willow, a hawthorn, or a dogwood7,10,11. Leave areas of bare soil in your garden bed or lawn so that mining bees have somewhere to nest10. Avoid using pesticides, or if you must, limit your usage9,10. Consider advantages and disadvantages before you start a honeybee colony, because this can create competition for native bees10.

1 Ascher, J. S. & Pickering, J. (2020). Discover Life bee species guide and world checklist (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila).

http://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?guide=Apoidea_species

2 Vermont Atlas of Life. (2021). Mining Bees (Genus Andrena). https://val.vtecostudies.org/projects/vtbees/andrena/

3 Fravel, L. (2022). Mining Bee (Andrena sp.) U.S. National Arboretum, Washington DC [photo]. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/2nbvYFn

4 Manher, S., Manco, F. & Ings, T. C. (2019). Using citizen science to examine the nesting ecology of ground-nesting bees. Ecosphere, 10(10), https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2911

5 Tsiolis, K.?(2023)?Nesting preferences of ground-nesting bees in commercial fruit orchards.?PhD thesis, University of Reading. https://doi.org/10.48683/1926.00113763

6 Herrera, C.M., Núñez, A., Aguado, L.O. & Alonso, C. (2023). Seasonality of pollinators in montane habitats: Cool-blooded bees for early-blooming plants. Ecological Monographs, 93(2), https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1570

7 Fowler, J. (2016).?Specialist Bees of the Northeast: Host Plants and Habitat Conservation.?Northeastern Naturalist,?23(2), 305-320, https://doi.org/10.1656/045.023.0210

8 Moisan-Deserres, J., Girard, M., Chagnon, M. & Fournier, V. (2014). Pollen Loads and Specificity of Native Pollinators of Lowbush Blueberry,?Journal of Economic Entomology, 107(3), 1156–1162,?https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13229

9 Rondeau, S., Chan, S.W. & Pindar, A. (2022). Identifying wild bee visitors of major crops in North America with notes on potential threats from agricultural practices. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.943237

10 Baldock, K.C.R. (2020). Opportunities and threats for pollinator conservation in global towns and cities. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 38, 63-71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2020.01.006 11 Bogusch, P., Bláhová, E. & Horák, J. (2020). Pollen specialists are more endangered than non-specialised bees even though they collect pollen on flowers of non-endangered plants. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 14, 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-020-09789-y