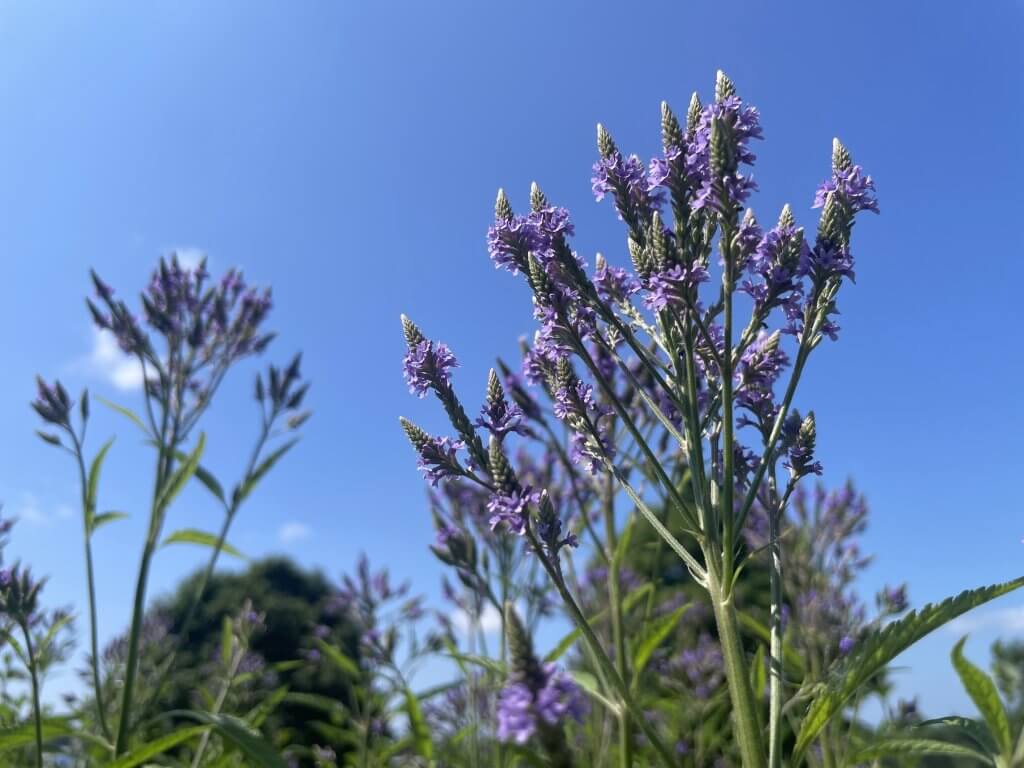

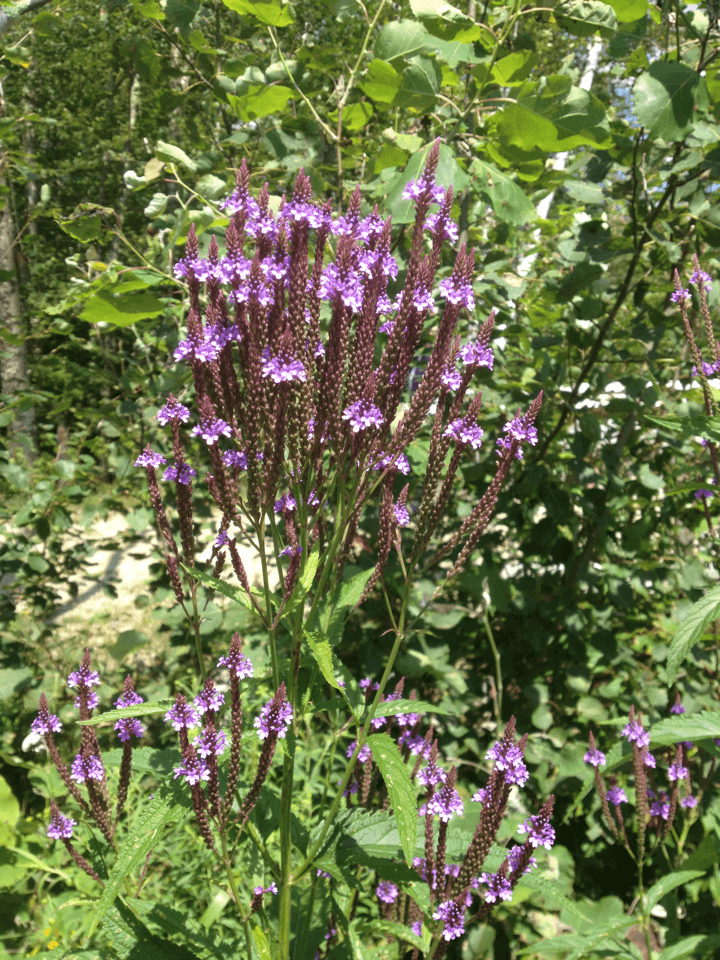

Blue Vervain, a Wild Wildflower

This guest blog is part of a series of articles written by Mount Allison students, as part of a partnership between Nature NB and the Applied Native Plants and Pollinator Conservation course. Thanks to Dr. Emily Austen and the students for this ongoing collaboration!

By Keeghan Stephens, Student at Mount Allison University

Native wildflowers are our environment’s naturally occurring flowering plants. These plants evolved and grew alongside other plants and animals, such as pollinators, perfecting a fragile balance with each other that helped the ecosystem run properly. Verbena hastata, or Blue Vervain, is one such native wildflower.

You may be familiar with these spires topped by purple flowers from driving past them in roadside ditches or from evening walks in wetlands and meadows. Blue Vervain plays an important role in our ecosystem as a popular stop for pollinators like bees, and as a stopgap for methane emissions in wetlands.

Blue Vervain is a hardy perennial wildflower that is native to regions spanning all of North America. In New Brunswick, it has long lasting and attractive blooms from July to September, and an impressive maximum height of five feet. As a wetland flower, it thrives in damp soils and open skies. Blue Vervain displays a wide array of interactions with other organisms in its environment, both pollinators and not. Its seeds are a target of birds like Cardinals and Juncos which disperse them across the landscape. Importantly, Blue Vervain is a popular stop for many pollinators, such as bees, whose populations are on the decline globally.

Planting wildflowers is a fun and effective contribution to supporting pollinator populations. When producing seed mixes to plant on your own property, Blue Vervain should be a front-runner. Other research involving this plant found that it was one of the plants most commonly visited by native bees in a wildflower patch (Abbate et al. 2024). The study emphasizes using the attractiveness of this flower to bring more generalist pollinators to flower patches. By drawing more generalist pollinators to the patch, Blue Vervain ensures that other plants in the patch are pollinated at a higher rate, supporting specialist pollinator species that might only rely on one plant in said patch. It also means that if one pollinator population is having a bad year, others are there to pick up the slack.

To learn more about planting and caring for Blue Vervain, consult these sources:

Blue Vervain Cultivation: Tips On Growing Blue Vervain Plants, Blue Vervain (Verbena Hastata) Plant Fact Sheet

Beyond its benefits to pollinators, Blue Vervain can also play a part in controlling climate change. The wetlands that Blue Vervain inhabits are methane-sinks, trapping the gas under layers of thick mud. Methane is a greenhouse gas 28 times the heating-trapping ability of carbon dioxide. Wetlands are responsible for a third of global methane emissions. According to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, 64% of the world’s wetlands have been lost, with more degraded; these degraded and lost wetlands are further responsible for a disproportionate amount of methane emissions (Ramsar, 2018; Evans & Gauci, 2023). Pristine and restored wetlands typically have plants which limit the amount of methane emissions, but wetlands damaged by invasive plants and development may have fewer native plants to fill this role and produce more emissions. Blue Vervain appears to play this role as a buffer plant, releasing no methane (Kao-Kniffin et al. 2010). Restoring our wetlands’ natural dynamics by planting native flora, including buffer plants like Blue Vervain can reduce emissions and help slow climate change (Evans & Gauci, 2023)

Blue Vervain is a truly remarkable plant. Not only is it beautiful, but it makes major contributions to the well-being of our ecosystems. These contributions range from being a pollination-promoter for local wildflowers, to cutting down methane emissions in wetlands. It is easy to focus on these standout organisms. All wildflowers are worthy of appreciation, however. Whether they have impressive flowers, play an outsized role in the ecosystem, or none of these things, it is good to remember that these organisms all have their place in the intricate web of our ecosystems.

Join the Seed Sitters Club for a newsletter by Nature NB, all about growing native plants!

Sources

75% of Earth’s land areas are degraded; wetlands have been hit hardest, with 87% lost globally in the last 300 years | The Convention on Wetlands, The Convention on Wetlands. (n.d.). Retrieved October 24, 2024, from https://www.ramsar.org/news/75-earths-land-areas-are-degraded-wetlands-have-been-hit-hardest-87-lost-globally-last-300

Abbate, A. P., Campbell, J. W., Grodsky, S. M., & Williams, G. R. (2024). Assessing the attractiveness of native wildflower species to bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) in the southeastern United States. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 5(3), e12363.

Evans, C., Gacui, V., (2023) Wetlands and Methane Technical Paper (Wetlands International)

Features, M. H. D. last updated in. (2014, November 8). Blue Vervain Cultivation: Tips On Growing Blue Vervain Plants. Gardeningknowhow. https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/ornamental/flowers/blue-vervain/growing-blue-vervain-plants.htm

Kao-Kniffin, J., Freyre, D. S., & Balser, T. C. (2010). Methane dynamics across wetland plant species. Aquatic Botany, 93(2), 107-113.

Kirk, S., Belt, S., & Berg, N. A. (2011, February). Blue Vervain Plant Fact Sheet. Western Native Seed. https://www.westernnativeseed.com/plant%20guides/verhaspg.pdf

Plant database. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin. (n.d.). https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=VEHA2

Ulyshen, M., & Horn, S. (2023). Declines of bees and butterflies over 15 years in a forested landscape. Current Biology, 33(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.030

Van Drunen, S. G., Linton, J. E., Kuwahara, G., & Ryan Norris, D. (2022). Flower plantings promote insect pollinator abundance and wild bee richness in Canadian agricultural landscapes. Journal of Insect Conservation, 26(3), 375-386.